The Background to Coal Mine Gas Risk Assessments

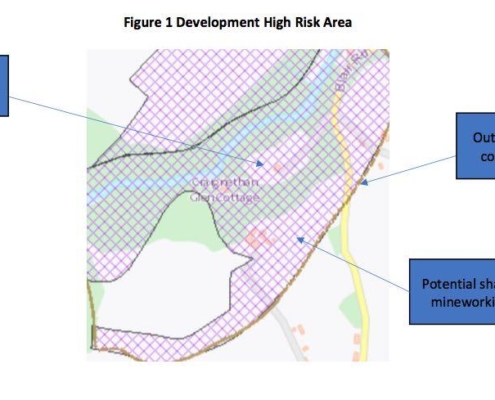

In 2013/14, a highly-publicised incident unfolded in Gorebridge, situated in Midlothian, Scotland. This incident brought to light the potential risks associated with the ingress of gas into residential buildings from underground mine workings, raising concerns about human health (NHS Lothian, 2017). The most common complaints were headaches, dry coughs, dizziness and anxiety.

The town is in a former mining area and the development was underlain by old mine workings with shafts present nearby. Further investigations showed there was mine gas ingress which resulted in the relocation of residents and demolition of 64 homes.

In Northumberland a similar situation also occurred with reports of illness that were symptomatic of exposure to high levels of carbon dioxide. Again further investigations revealed that mine gas was seeping into the properties causing illness. A detailed site investigation followed which highlighted the exact points of gas ingress. The investigations revealed that the gas was only entering through unsealed open ducts containing water pipes. Fortunately once the openings were correctly sealed the properties were safe to return to.

Following these incident, the Scottish Government commissioned research to investigate the broader prevalence of similar cases. Their findings revealed a limited number of incidents occurring in Scotland, the wider UK, and even internationally since the 1950s. This research also underscored the inadequacy of existing standards and guidance on ground gas, particularly concerning factors related to mine gas risks. As a result, it recommended the supplementation of these standards and guidelines. The purpose of this guidance is to shed light on the aspects related to mine gas risk assessment for development, direct stakeholders to existing resources, and advocate for best practices.

The term ‘mine gas’ used in this report specifically refers to ‘coal mine gas’ with the principal components being methane, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulfide and deoxygenated air.

The Gorebridge incident further emphasised the significance of incorporating reasonably foreseeable changes into the mine gas risk assessment process. For sites where there is a potential presence of significant mine gas sources, the risk assessment should remain a dynamic document until the final design is confirmed.

It is also important to ensure that external factors e.g. climate change and regional groundwater conditions should also be thoroughly understood whenever possible.

It’s also worth understanding that whilst the predominant risk in the UK is from Coal Mining activities, other types of mines, such as oil shale, metalliferous, and rock mining (CIRIA, 2019), could potentially lead to gas emissions from the ground.